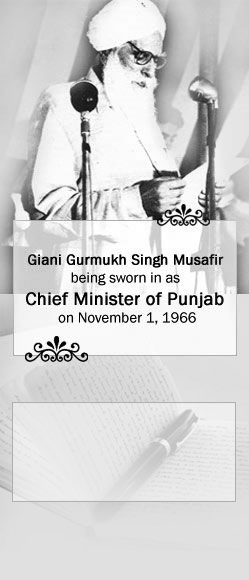

Giani Gurmukh Singh Musafir

Poet, politician, and freedom fighter

A letter that was to be written – Mulk Raj Anand

Giani Ji,

This letter to you was to be written a few months ago. But I was in America on a lecture tour and could not write. Now, you will not receive it. I hope it will go to many of our friends. Actually, I meant to send you some words on your last birthday. I am sad that these words are now being put down after you passing away.

Those of us who have accepted the challenge of death, and consider it to be the transition of Worlds, temper our sorrow with the realization that the flame inside us if it is there will burn in other hearts and illuminate people’s consciousness. And, from my glimpses of the flame, which burnt in you after these years, I am sure that the light you shed will kindle the hearts of the new young.

I think of you mainly as a poet. I know that you got involved in politics very early in your career. That was because to your poetry, in the form of mellow words, which translate adolescent sentiments into once matopoetic syllables did not mean much. You conceived poetry as the vehicle for the great urge for freedom, which possessed our generation. Not only the vague ideal which people talk about on the platforms of the world to get themselves noticed, but the content of freedom. To be sure, the fundamental part of this content was to us political freedom, the aspiration of our people to emancipate themselves from centuries of suppression under one-man rule and to emerge into human dignity. But we included many other freedoms implicit in the total freedom. In our view, the freedom of the individual to grow, to learn, to live in the full enjoyment of the splendors of our heritage, to create the necessary worldly goods for sustenance, to awaken in us all the highest consciousness of life, in all its terror, refulgence and its beauty. Thus, your poetry became a series of footnotes to your rare speeches.

In fact, I have the impression that, in later years, you did not say much on any platform. You user to write down your verses when somebody else was speaking. I remember you doing this in the Peace Conference in Baku, as also during our journey together from Tokyo to Kyoto, and in the Mavlankar Hall when a seminar was going on. And when you read the poems to me, I was confirmed in my hunches that to you the eloquent speeches were only the inspiration for these stirrings deep in your temparement, which expressed your faith in life.

Quite recently, during one of my journeys abroad, I came across a young man, a poet, who told me that he wondered why I was able to utter words with such facility. He said he himself felt that words had no more meaning in our age. He confessed he had no friends. And he preffered to remain aloof from contact with people. He didn’t see the use of communication at all. I asked him whether he did not feel anything when he saw, in the newspapers, that the arms race was going full speed ahead, that the merchants of death were exploding bombs, from which the normal background radiation in every test, caused five hundred thousand unborn children to suffer gross mental and physical defects, and doubted my statement and remained dumb. I asked him whether he was married and had a child. There upon, he confessed that he had a girl who had left him.

And people did not seem to him to be worth worrying about. I told him that it was strange he had talked to me. He answered that I seemed to him to be a descent sort of fellow. I was constrained to say to him, not from modesty but from a genuine hunch that there were millions of decent people in the world in spite of all the men of violence, of greed and terror, that, in facts, human beings had survived in all these ages, in spite of half a million wars, thoug little acts of kindness of tender mothers, dedicated doctors and nuns working with humble people in the wilds.

The poets of our time were committed to life. They did not complain about people not loving them. They loved the people presuming that men and women can love not only through sexual love, but also through the exuberant passion for life itself.

As one of the pioneers of this commitment to life, you intensified the emotions of all of us, and instilled energies into yourself and others. You were, therefore, the new kind of poet, like Lorca, Neruda and Faiz who believed in the solidarity of human beaings, in the struggle for life and more life.

And it is because you remained in touch with your comrades in this struggle, even in your advanced age, that your memory will remain a vital inspiration for us. To persist in the struggle for those freedoms which the enemies of promise still deny to the emergent peoples, to continue to recite your verses, and utter, our own words of tenderness.

I only hope that your spirit will communicate itself to many of our youth, which seem to feel uninvolved from the feeling that none cares for them.

At any rate, I want your poems to enter the very air of our landscape, to inform our life breath, to usher us into hope.